‘Artuke’ rhymes with Y2K and is pronounced like R2D2’s brother, both of which are better names than the one sported by the guy who owns Artuke Bodega (Kike Blanco), who is grateful for his own brother Arturo. Because without the portmanteau of their two names, he’d be enologo at Kike Bodega, and this would be a whole different column.

‘Artuke’ rhymes with Y2K and is pronounced like R2D2’s brother, both of which are better names than the one sported by the guy who owns Artuke Bodega (Kike Blanco), who is grateful for his own brother Arturo. Because without the portmanteau of their two names, he’d be enologo at Kike Bodega, and this would be a whole different column.

As it is, it’s a tale of two Riojas, referred to by the brothers as ‘new’ Riojas, one of which wound up being an old Rioja style rediscovered.

But I’ll get to that.

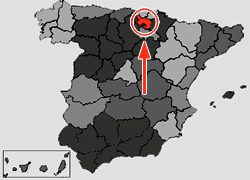

First, Artuke is located in the Basque province of Álava, and the de Miguel Blanco family has been cultivating wine grapes here for well over a century. This territory is not a part of the Autonomous Community of La Rioja, but one of the two satellite provinces that encompass the growing region of Spain’s most famous AOC; the other is Navarre. Primary grapes are Tempranillo, Garnacha (Grenache), Graciano and Mazuelo (Carignan) for the stylish reds and Viura and Garnacha Blanca for the sharp, fruity whites.

Like most Old World wine regions, Rioja has been working overtime to maintain a predominant position the world’s wine stage, and part of the reinvention process has been a re-think of style, at least for the export market. Traditionally, a red Rioja was something that looked, smelled, tasted—and as overall organoleptic ordeal—simply ‘felt’ old. It was a leathery interplay of wood, grape and oxygen; the best were remarkably subtle, often elegant, but a working man’s Rioja could come across as thin and oxidized—like acidity interred within an oak sarcophagus. They were, of course, intended to be food wines, made for a food culture, and even today, 70% of Rioja is consumed within Spain and three-quarters of that inside restaurants.

But as beloved as the old style was in the pintxos cafés of San Sebastián, the enotecas of Barcelona and the designer restaurants of Madrid, the world evolves as it revolves and in recent years, global tastes have moved to a somewhat opposite style of red wine—one that is fruit-sweet, dense and delovely, often high in alcohol and hugely extracted, wines with less barrel and more fun.

And a gradual change began to take hold in Rioja. Step by step, mote by mote; nothing too noticeable, nothing to put the jende zahar off their Gran Riserva. Old casks were replaced with new, and the time the wines hibernated within them lessened. Bottles were held back for shorter periods. At La Rioja Alta, the progression went from 20-year-old barrels to eight; from six years in barrel / six in bottle for 904 Gran Reserva to 5/5, then 4/4.

Even the most die-hard traditionalists have altered the company line a bit: At the bullheaded bastion of beaten boulevards, López de Heredia bodega, the ‘Philosophy’ tab on their website has been revised to say, “Our daily tasks are rooted in tradition, yet at the same time based on our deep belief in the validity and modernity of our methods. By ‘tradition’, we do not mean immobility and opposition to change; rather a dynamic and aesthetic concept in maintaining eternal principles and criteria.”

In other words, “If you want fruit bombs, we’ll give it a go.”

At Artuke, the Hermanos Blanco have tacked direction, focusing the winery on small vineyard plots near their village of Abalos in the high elevation foothills of the Cantabrian Mountains. This is high Basque country, where the cuisine, the culture and even the language is distinctly un-Spanish.

The two Artuke wines I tried were twin interpretations of the ‘new’ Rioja, both different from each other and both different from the classically-styled Riojas that were status quo when their grandfather worked the land.

Earlier, I referred to the entry-level Artuke (around $12) as an ‘old Rioja style rediscovered’, and that’s because at first whiff, the fact that it is produced in using the Beaujolais-favored technique of whole-cluster carbonic maceration, is obvious: The wine is bombastically fruity, with fresh, confected notes of ripe plum, concord grape and concentrated rose water—the result of being made in concrete tanks under the influence of carbon dioxide, which allows for the extraction of more fruit flavors and less tannin. The wine is, as a result, refreshing and rather simple, finishing mid-palate as though it took a swing from Lizzie Borden’s axe. All of which are (I imagined) anti-Rioja trademarks. But as it happens, I imagined wrong: This is the original Rioja, before crianza and Gran Reserva came into vogue. This is, I was told, the sort of wine that the Blanco’s grandfather Miguel would have made.

Pies Negro 2011 leapfrogs the generations. Produced from Tempranillo (90%) and Graciano from vines nearly a century old, the wine is aged for fourteen months in a combination of new and old oak tinas, bringing out some of Rioja’s prototypical earthiness and dried-herbal-ness, but under a blanket of black cherry and cassis. I thought the wine showed a bit too much bitter tannin at the finish, enlivened by a bright acidity, but still appearing as a non-integrated crate.

Pies Negro 2011 leapfrogs the generations. Produced from Tempranillo (90%) and Graciano from vines nearly a century old, the wine is aged for fourteen months in a combination of new and old oak tinas, bringing out some of Rioja’s prototypical earthiness and dried-herbal-ness, but under a blanket of black cherry and cassis. I thought the wine showed a bit too much bitter tannin at the finish, enlivened by a bright acidity, but still appearing as a non-integrated crate.

Time—as it does in all things ‘Rioja’—will tell.

Meanwhile, ‘Pies Negro’ may translate to ‘Black Feet’—an homage to the método tradicional of crushing grapes by foot—but somebody should clue in the Brothers White to the American tradition of not advertising Negro wine made by a Kike.

What is the alcohol on this wine? 14.5% – 15%?

14% on the Pies Negro, 13% on the Maceración Carbónica.